First statewide tracking system created to better Iowa’s sexual assault kit testing capabilities

4,275. That was the number of unsubmitted, untested sexual assault kits in Iowa in March 2017.

Before then, no one in Iowa knew that number. Not hospital staffs, not the state’s crime lab, not law enforcement agencies.

Sandi Tibbetts Murphy, director of the Crime Victim Assistance Division (CVAD) of the Iowa attorney general’s office, said “many of them were just sitting in locked evidence rooms at local police departments,” and some were destroyed due to a lack of knowledge on storage procedures or damage from flooding.

But the main reason no one had an exact figure? There was no system in place to track how many kits were being collected and how many were being submitted for testing.

Tibbetts Murphy said the lack of tracking and longer waits to receive results from the Department of Criminal Investigation’s Crime Lab both led to a backlog of sexual assault kits.

This also meant that survivors who chose to have their kit tested didn’t have a clear way to know where it was or when they would get the results.

Through a federal grant initiative called the National Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (SAKI), Iowa received two grants in 2015 and 2016 totaling $3 million to identify the number of untested kits, have them tested and develop a tracking system to prevent another backlog.

In the first two years of the project, CVAD inventoried the untested kits in the state, asking Iowa’s 387 law enforcement agencies to report untested kits in its possession in a survey that received 100% participation.

Tibbetts Murphy said the kits weren’t tested if the survivor was anonymous, if the kit had documentation showing the survivor did not want the kit tested, or if it was determined the kit would not bring probative value to the case. This elimination process left 1,606 kits that would be sent to a private lab for testing in batches over the next four years.

Of those kits, 852 had sufficient DNA to enter into an FBI nationwide database, which found 294 “hits,” or matches to DNA in the database. So far, the findings have led to four criminal cases and two convictions.

But with the kits dating from 1992 to 2016, Tibbetts Murphy said most cases were “at least 10 to 15 years old” and many survivors were not interested in returning to that traumatic experience after years had passed.

Alongside the need to clear the backlog was the need to prevent another one.

Iowa selected Stacs DNA, a Canada-based sample tracking company, and its Track-Kit system to maintain records of the sexual assault kits collected and tested in the state.

Track-Kit was implemented in five states before Iowa, and after working through pandemic delays, the rollout was completed by October 2020. Iowa was the first state to require a mobile-friendly version of the system.

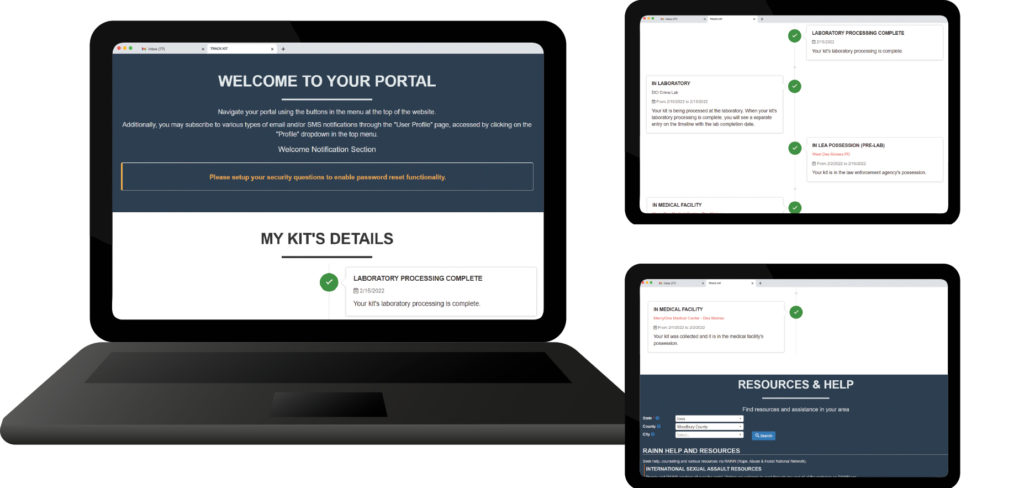

Through a test environment used for training, Mike McDonald, sexual assault crimes coordinator at CVAD, showed the Business Record how Track-Kit works.

A closer look at Track-Kit

When a survivor logs on to track their sexual assault kit, they see a page that says “Welcome to your portal” and “My kit’s details.” Nothing mentions sexual assault – and that’s on purpose.

The menu at the top includes a page telling survivors how to clear the site from their browser history as well as a red exit button that quickly closes the webpage. Below the welcome message is a simple timeline in reverse chronological order, showing where the kit is currently.

Each kit tracked by Track-Kit has a bar code that is scanned every time the kit changes hands.

For a kit that has completed the tracking process, survivors can scroll to the bottom of the timeline and see when it went from the hospital to local law enforcement, to the crime lab if they consented to testing, and back to law enforcement for storage.

Built into the tracking site is also a resource section that details services available in each county as well as contact information for the hospital, police department and county attorney’s office overseeing a survivor’s kit and case if they choose to report.

If a survivor was anonymous before Track-Kit, they couldn’t come forward later because they didn’t know which kit belonged to them and nor did the law enforcement agency storing it or the hospital that collected it.

Now each kit has a consent form with information clarifying the survivor’s rights on testing, reporting to law enforcement and storage of the kit and explaining how to register for Track-Kit.

McDonald said Track-Kit gives survivors a sense of transparency in the testing process for the first time.

“The victims that want and choose to follow where their kit is in the system, they’re able to do that without having to keep calling and hounding on law enforcement or their advocates to try to find that information out,” he said.

The tracking system will also allow McDonald and CVAD to check how many untested kits are in Iowa at any given time and better understand the reasons they aren’t being tested.

Changes beyond Track-Kit

Between the implementation of Track-Kit and parallel changes in legislation and at the state’s crime lab, Tibbets Murphy said the attorney general’s office and the lab are confident these will safeguard against another backlog in the future.

In May 2021, Gov. Kim Reynolds signed two laws, one creating a sexual assault forensic examiner program to provide uniform training and resources to health care professionals, and another formally establishing a tracking system for sexual assault kits and ensuring future funding for the program with the federal funding and SAKI testing program concluding in September 2021.

The legislation mandates the use of Track-Kit by Iowa law enforcement agencies and medical staffs, and changed the requirement for how long law enforcement stores sexual assault kits to 15 years.

At the state’s crime lab, supervisor Mike Halverson said the recent changes had been “on the agenda” before SAKI, and just happened to fall during the time Iowa was working on the testing project.

All DNA testing for Iowa law enforcement agencies is done by the crime lab; approximately one-third of its caseload is testing evidence from sexual assault kits. With high volumes of cases, Halverson said its backlog for all DNA testing meant an average turnaround time of six to nine months for test results.

But as of May 2021, he said the turnaround time has been reduced to around two months.

New state appropriations for the lab supported hiring several more forensic scientists over the last few years, and through federal funding in 2018 and 2019 the lab participated in a process efficiency program called Lean Six Sigma.

The program instructors worked with lab staff to reevaluate its processes for all of its DNA testing, such as how backlogged cases are assigned and having the forensic scientists rotate responsibilities rather than performing the multiday testing process on each case.

Halverson said the changes to staffing and to the processes helped produce results faster without compromising high-quality, trustworthy results.

There is still a backlog, he said, but it’s much smaller than it used to be and is the result of variations that the lab expects, like receiving 25 cases from one police department on the same day, for example.

“When we talk about turnaround times and we talk about backlogs, we always want to talk about a range of time and an estimate over that time,” he said. “It’s really not accurate to pinpoint it to one specific day or one specific week because there is that fluctuation that happens routinely.”

Beth Barnhill, executive director of Iowa Coalition Against Sexual Assault, said the new transparency and clarity on where a kit is and about how long testing will take is a beneficial resource for survivors who choose testing, but that doesn’t address everyone.

She said for the many survivors who don’t want to use the criminal legal system, Iowa should consider other avenues to resolve a sexual assault case, such as restorative or transformative justice.

Restorative justice typically takes place within the legal system, with the survivor expressing the effect of the assault to the perpetrator and asking them to acknowledge the harm they caused.

Barnhill said she has seen transformative justice used in smaller communities, including the Meskwaki Settlement in Iowa, and focuses on addressing the harm to the perpetrator’s relationship with the survivor as well as the larger community.

Being outside the traditional legal system, she said that scaling transformative justice isn’t a clear path, but that it’s worthy of the conversation.

“I don’t have the answer, but I think it’s something that we need to talk about some more, about what we can do for people who want that,” she said. “Because we hear that from survivors all the time: ‘I don’t want him to lose his job. I don’t want him to wind up on the sex offender registry. But I do want him to know that he hurt me. And I want to know that in some manner there’s something in place to make sure … that he won’t do that to anyone else.’”

History of SAKI

The National Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (SAKI) started as a federal pilot program in Detroit in 2009 when assistant prosecutor Robert Spada discovered more than 11,000 untested sexual assault kits from 1984 to 2009 backlogged in a warehouse at the Detroit Police Department. Wayne County prosecutor Kym Worthy led the initiative to clear the backlog, and one decade later in 2019, her office finished its review and had tested 98% of the kits

The federal program is now administered by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance and 71 states, counties, cities and police departments have been or are SAKI sites.

As part of the initiative, the Iowa Attorney General’s Crime Victim Assistance Division formed a multidisciplinary team with representatives from their division, the Department of Criminal Investigation and its crime lab and Iowa Coalition Against Sexual Assault to decide the testing protocol for the 4,275 untested kits identified by the survey of Iowa’s law enforcement agencies.

The Iowa SAKI website launched in 2018 with resources for survivors, law enforcement, prosecutors and advocates. To learn more about Iowa’s SAKI project, visit iowasaki.com.