How the sudden transition to online learning in 2020 pushed four Iowa school districts to arrange internet access for students in need in a matter of months.

“Broadband internet should be widely available like any other utility.”

Four Iowa school districts from across the state echoed this declaration after reviewing a year where they saw how quickly home internet access for students became an absolute necessity.

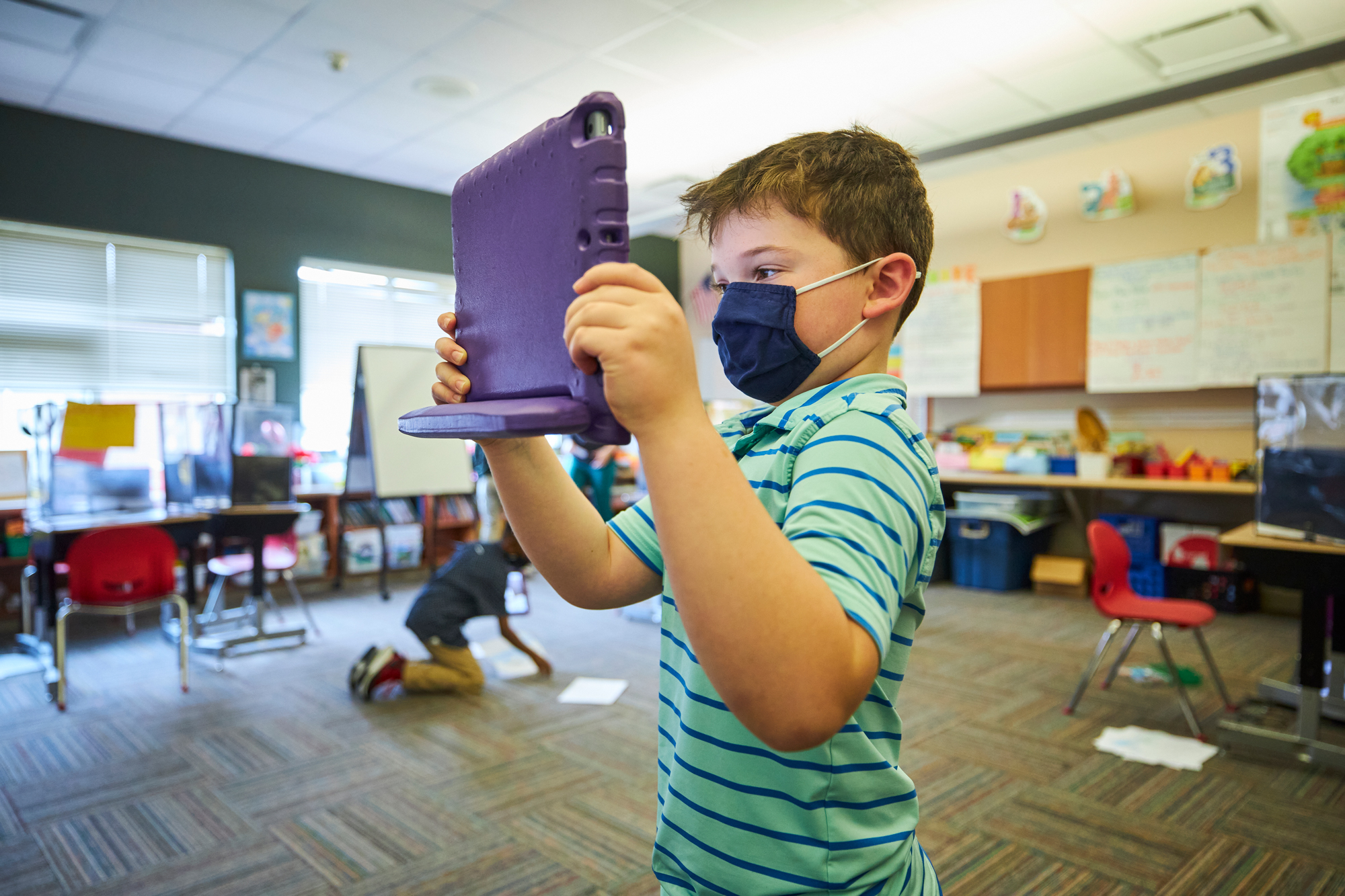

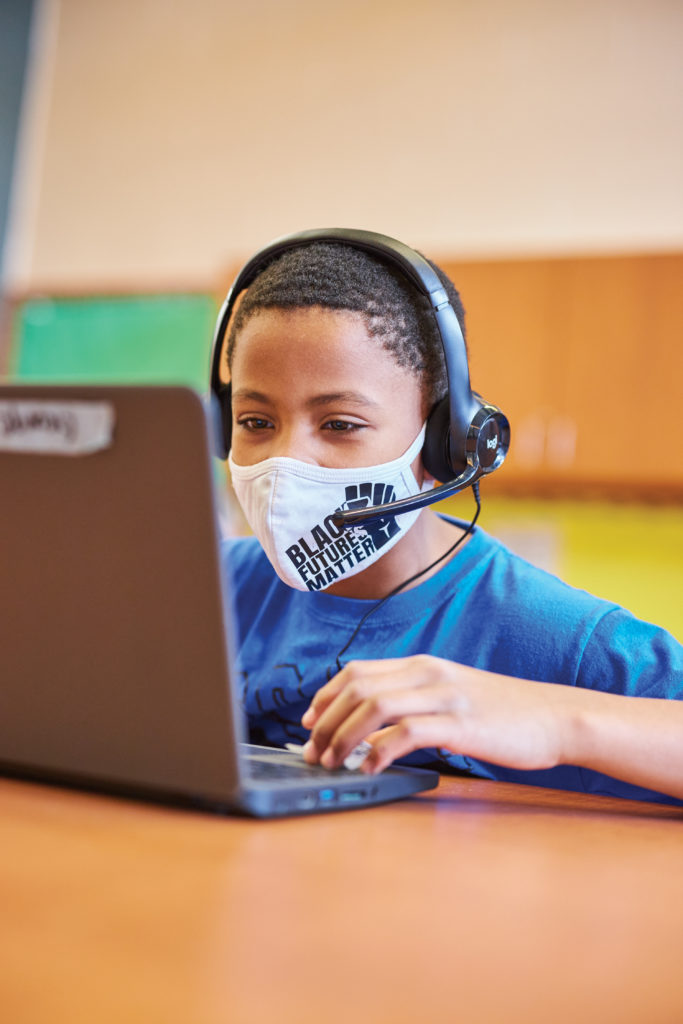

Faced with hundreds or more students from preschool to high school who lacked a reliable way to attend school virtually, the pandemic obliged districts to expedite and revamp their technology plans. In response, they asked others to do the same.

Des Moines Public Schools learned in late March 2020 that more than 6,000 of its students had limited or no access to broadband internet. That number prompted Dan Warren, the district’s director of technology, to start searching for solutions.

“I just started making calls and I knew Mediacom was right in our backyard so that was the first call I made, just asking ‘What can you do to help us?’ … We started talking about the Connect2Compete program and what we can do to get this in as many homes as possible,” Warren said.

Subscribers of Mediacom’s Connect2Compete program pay $9.95 per month to have broadband internet service in their home. The costs and fees of equipment and installation are also waived.

Families typically sign up for the program by contacting Mediacom independently and must have a child who receives free or reduced-price lunch to be eligible — that is, until 2020.

“[Des Moines schools] asked Mediacom to continue adding more families individually, which we did, but to also allow the school district to be the customer purchasing ‘bulk’ service, in effect; and by doing so, have the school select the student households where Mediacom would be assigned to go install and activate new service,” Mediacom Communications Director Phyllis Peters said.

With this agreement, the district covered the cost of connections for 704 families, which helped about one-third of the students in need, according to Warren.

A partnership of this scale between a school and an internet service provider was a first of its kind, but that status did not keep for long. The success of the effort led 13 more districts, including Urbandale, Marshalltown and Davenport, to partner with Mediacom in 2020.

In addition to growth from school partnerships, Mediacom added more families who subscribed to Connect2Compete independently. Peters said parents in need started to call Mediacom asking for help once they learned their students would move to online learning. Between March 31 and December, 3,504 participants joined through a school partnership or by subscribing independently — five times the number of participants as before.

Partners navigate installation, communication

Due to the sudden mass interest in Connect2Compete installations, Mediacom upended its normal procedures to accommodate the pandemic.

To avoid unnecessary contact, technicians mostly instructed families on setting up their connection through a window or door rather than entering their homes. Peters said the technicians did more “front-end” work preparing modems and including the necessary instructions and passwords for the family before making contactless drop-offs.

“The goal was to not leave unless we knew that families knew how to connect to the internet,” she said.

As more districts started using the scaled-up version of Connect2Compete, the initial idea of bulk installation began to take shape. While installations were concentrated in the Des Moines metro area, Mediacom coordinated efforts with several districts across eastern and southern Iowa.

“It could happen simultaneously — hundreds could be getting installed in Des Moines at the same time that hundreds could be getting installed in Waterloo,” Peters said.

School districts helped families navigate installations in their own way. In the frequent case of a language barrier between the family and the Mediacom technician, schools took the lead on providing interpretation.

The Saydel Community School District serves about 1,300 students in the Des Moines and Ankeny areas, including numerous Spanish-speaking families.

“We have several individuals that can interpret in the district, so we sometimes had to coordinate with Mediacom to have one of those individuals available, or [the interpreter] could call the family along with the Mediacom representative to [tell them] when the installer was coming,” Saydel Director of Technology Chris Stammerman said.

The Des Moines school district provided the same type of service for its bilingual families, who in total speak more than 100 languages. Through its role as a partner of the nonprofit Coalition for Community Schools, the district employs “bilingual family liaisons.” In the event of a language barrier, they visited families’ homes and through a window or door walked them through the setup.

“Sometimes technology is like an entirely new language on its own, and for a lot of our families, this was new to them. Our team would just make sure that they had the support they needed,” said Allyson Vukovich, director of community schools for Des Moines schools.

Another barrier to installation for bilingual families was that parents were often still going to work early on in the pandemic.

“We thought in March and April people were staying at home and that people weren’t working. Yet we would find that this population tended to be many of the essential workers, so the parent wasn’t at home and we couldn’t install it if you’ve got a sixth grader and an eighth grader there but not a parent,” Peters said.

Vukovich said it was situations like this as well as the fear families felt when much was unknown about COVID-19 that proved the importance of connecting with students and their parents and building a “bridge between the school and the community.”

Schools find flexibility in hotspots

Mediacom’s initiative was not alone in its popularity among schools. Hot spots were ubiquitous among families pre-pandemic as a backup or sometimes sole source of internet connection. In 2020, they became a tool to address school districts’ widespread needs.

Both the Waterloo and Des Moines school districts were looking at about 20% of students without reliable internet access. Among Saydel families, Stammerman said the survey revealed that an estimated 10% of families needed assistance.

Districts flocked to hot spots mainly because they could go anywhere a student did.

“We might have kids going to babysitters or day cares or kids going to family members that did not have internet access. What this allowed us to do is to sign them up through the building [and] assign them a hot spot so they could take it wherever they needed to go,” Warren said about the need for the devices.

Stammerman said Saydel students and their families tended to move around even before the pandemic, so hot spots were a must-have for getting them connected.

“Our population is a little more mobile. We have a lot of students coming in and out of the district [and] we have a lot of families move, so we wanted something a little more portable and flexible,” he said.

More than 50% of Saydel students are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch, and Stammerman added that it is often these families who are regularly moving.

“[Parents’] jobs tend to fluctuate more often, so they’ll potentially go in and out of employment. When they do that, they tend to move a lot and oftentimes that’ll be out of a district because they’ll move into an apartment or rental,” he said.

Before putting hot spots into students’ hands, districts first worked through issues with getting them delivered. Many major cellphone providers responded to schools’ needs with programs supplying hot spots. But at first, demand far exceeded supply.

The Waterloo Community School District partnered with both Mediacom and hot spot providers, as did the Des Moines and Saydel school districts. Waterloo schools’ Director of Technology Matt O’Brien said availability was a key factor in deciding how to connect each of the district’s 1,772 students in need.

“Mediacom did a great job of prioritizing installs, but there was still a bit of a lag in getting service connected. On the flip side, hot spot availability was initially pretty bad. Thus, we would connect families with Mediacom service if Mediacom was able to service them. As our numbers grew and we got more hotspots in stock, we would provide whichever service we believed would get families in need connected faster,” O’Brien said in an email interview.

Stammerman and Warren said their first hot spot shipments reflected the stress on the supply chain. Verizon sent refurbished hot spots to Saydel, and Des Moines got 1,200 phones from U.S. Cellular that were configured to function only as hot spots.

Availability improved as the year went on, which was good news for Des Moines schools. Warren said he partnered with two other hot spot providers to get a total of just under 7,000 of them.

Des Moines needed that many hot spots to accommodate families in the district with multiple students needing to attend online classes.

“When you get three to five people connected to even a hot spot, it can be problematic, so in some families we’ve had to give them two, sometimes three hot spots to make sure that they do have access because there’s a lot of video and things like that involved in online learning,” Warren said.

Pandemic showcases rural disparities, need for change

The Des Moines, Saydel and Waterloo school districts all relied on hot spots to connect their students, but their more accessible locations meant other options were available too. This was not the case for the Cardinal Community School District in rural Eldon.

Enrollment at Cardinal schools totals about 900 students who are from five communities in southeast Iowa, all with populations less than 1,000. As Superintendent Joel Pedersen said it, none of their students will be found walking to school.

Learning was optional for Cardinal students after the pandemic began, largely because a survey showed about a quarter of students did not have broadband internet access.

“We pooled as many resources as we could. We tried to connect with kids, but the engagement was not very good. Part of that was we didn’t require [participation] because we didn’t have the infrastructure in place. How can we give a kid a grade if they don’t have internet at home?” he said.

Knowing that students did not receive quality instruction in those months, Pedersen said it was “hard to not want to get kids back in school” in the fall.

In the search for solutions for the fall, Pedersen inquired about partnering with Mediacom, but learned that its broadband network only reached far enough to help about 10 Cardinal students. That meant supplying hot spots to families who needed them and bringing students back to in-person learning with measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. By the spring 2021 semester, fewer than 10% of students were still operating remotely.

According to BroadbandNow, nearly 90% of Iowans have broadband access at the minimum speed required by the FCC of 25 megabits per second. But broken down by county, the numbers start to show disparities.

Broadband coverage in both Polk and Black Hawk counties is 98%, per BroadbandNow. The four counties where Cardinal students come from lag behind that level by at least 10 percentage points; in Van Buren county, fewer than half of the people can access broadband.

Families from all four districts do collectively share the struggle to find affordable internet. BroadbandNow reports that just 18.5% of the state has access to internet plans that cost less than $60 per month. And with higher levels of poverty in these districts — about 60% of Cardinal students and 75% of Des Moines students — the pandemic may be a catalyst for addressing longtime issues.

“We really haven’t changed from the broadband desert that we had before the pandemic, we’ve just acknowledged that it’s probably a bigger problem,” Pedersen said.

The push to move to a distance learning model under time pressure forced everyone from administrators to students and parents to catch up with technology faster than originally planned. Still, despite the chaos of 2020, it has inspired all these school districts to consider keeping online options even when the pandemic abates.

For Des Moines and Saydel schools, every student has their own computer and content is available online, making distance learning a flexible option if students need it.

“We have some students that for one reason or another can’t necessarily be in the building, and we want to be able to provide education to those students in a form that works for them and that supports their learning,” Stammerman said. He also said Saydel is “very likely” to continue providing internet to families in need through hot spots or the Mediacom partnership.

O’Brien said many Waterloo students prefer in-person learning, but the technology innovations of the last year stand to help students and teachers.

“Connected students allow learning to continue on snow days and allows teachers to use effective strategies like differentiation and “flipping their classroom” to provide some instruction via technology so their class time is freed up to work with students to answer questions and supplement instruction,” he said.

The Cardinal school district plans to “reimagine what summer school” looks like for rural Iowa students. Using hot spots to conduct summer lessons virtually spares both teachers and students the need to travel to school. Pedersen said it would also help the school check in on students over summer break.

The superintendent said he was optimistic about this possibility since the pledge from Gov. Kim Reynolds to expand broadband internet to unserved areas in her Condition of the State address in January.

“There’s no reason the whole state shouldn’t have quality, affordable internet, and that’s going to take a public-private partnership. But I think that the pandemic has shown us how important [it is] that people have broadband internet,” he said.

Going forward, Pedersen said he wants his school district and all of Iowa to continue striving to create an equitable experience for everyone.

“I think we want our whole state to improve and grow. … Anywhere you live in Iowa should be a quality place that has all the things that allow you to live there if you want to,” he said.

What did the derecho do to internet access?

Cedar Rapids ISP ImOn shares how it got customers back online after getting the worst of the storm damage

On Aug. 10, a type of storm that most Iowans had never heard of, let alone seen, barreled across the state, taking out most everything in its path, including power to all of Cedar Rapids.

And when the power goes out, the internet follows.

Lisa Rhatigan, vice president of marketing for ImOn Communications in Cedar Rapids, said internet service typically returns once the power does, but the fact that the whole city went dark after the derecho made it a “100% different situation.”

More than 1,000 “strands of line” came down with the power lines and 26 miles of cable at ImOn’s plant was damaged or blew away in the storm. The internet service provider also has 30 “hubs,” which help serve different areas — all 30 were damaged along with their nine backup generators.

Before anyone learned these numbers, though, ImOn needed to survey the damage. Rhatigan said ImOn has an agreement with Alliant Energy that in the event of a power outage, ImOn’s teams would wait to go out until after Alliant had finished restoring its grid.

The widespread and severe damage in Cedar Rapids meant this time it took as long as two weeks for some people to regain power.

In good news, internet connection returned automatically for 70% of ImOn customers when their power came back. Rhatigan said automatic restoration happened for most customers partly because ImOn’s core network system did not go down, so the internet service provider never lost its connection to the internet.

Customers who lived in neighborhoods where the lines were above ground and subsequently knocked down by hurricane-force winds made up the group that needed more work to have their internet restored.

Some of ImOn’s fallen lines lay beneath piles of debris waiting to be dug out. With conditions like this awaiting maintenance teams, Rhatigan said as a smaller local company they brought in contractors to help survey the situation.

“We have to do a visual look to find out where the damage is. And the National Guard was there clearing debris, so we didn’t have a visual on some of our network. Getting that done, just the scope of the damage and trying to identify that and get it done … was pretty tough,” she said.

During this time when Rhatigan said there was “understandable frustration,” ImOn looked for ways to help the community through the crisis.

ImOn offers three community Wi-Fi areas powered by hot spots and dispersed throughout the city. Usually they are only available to customers, but all restrictions were removed, extending unlimited access to anyone who needed it. The ISP also set up internet service and cleaning for a socially distanced internet cafe.

Rhatigan commended Cedar Rapids residents for their resolve and positive attitude throughout the situation and said ImOn felt its company approach worked.

“Let’s take care of each other, let’s take care of our customers and let’s take of our community. When we approach things and stick true to our values and who we are, we’re effective,” she said.