Iowans launch network to connect providers, communities seeking better service

Recall the last year your home had dial-up internet service, the once great, shining beacon of communication in America.

As you nudged your modem awake, a sound that an Economist writer once described in 2007 as “the distorted screams of two modems introducing themselves” disturbed the air of your at-home office or kitchen, where the family computer sat. As a DSL service user, no one else in your household could access the phone line — in fact, perhaps you may have disconnected a landline telephone to plug the computer modem into a phone jack.

Service: A Glossary

DSL (digital subscriber line): Internet provided over copper landline telephone lines, by phone companies. Download speeds range between 5 and 35 megabits per second, and upload speeds are in the 1-10 mbps range. Often bundled with home phone service.

Cable: Internet provided over copper coaxial television cable, by TV cable companies. Download speeds range between 10 and 500 mbps, and upload speeds range between 5 and 50 mbps. Speed sometimes slows during “peak use” times (as your neighborhood turns to Netflix after work, industry tracker BroadbandNow notes). Often bundled with TV service.

Fiber: Internet provided over fiber-optic lines. Communities can singularly invest or partner with other communities or private businesses to install and manage high-speed fiber-optic lines. Download and upload speeds are typically the same, and range between 250 and 1,000 mbps.

Source: https://broadbandnow.com/guides/dsl-vs-cable-vs-fiber

More than anything, perhaps you remember waiting for your news, entertainment or search results to load. You likely would not have bothered to rely on DSL to access your bank accounts or bills. If you were a small business owner, you certainly would not have relied on DSL to manage payments to your company.

By 2013, the Pew Research Center had determined that only 3 percent of Americans accessed the internet through DSL connections; 70 percent got there through broadband. It begs the question of whether the remaining 27 percent of Americans could access the internet at home just six years ago.

Today in rural Iowa, the question is whether existing connection speeds are worth accessing at all.

In 2018, Pew found 58 percent of rural Americans reported access to high speed internet — defined by the Federal Communications Commission as 25 megabits per second — as a problem in their area.

Broadband access is regularly cited as a key factor in a community’s economic development. In her 2019 Condition of the State Address, Gov. Kim Reynolds requested $20 million in the next two years from the Iowa Legislature to support broadband infrastructure development.

“It’s virtual connectivity that has become essential. Businesses, schools, hospitals and even our combines rely on high-speed internet,” Reynolds said in January.

In Iowa, the Community Broadband Action Network is moving to change things for rural areas.

The Advocates’ Network

Before introducing panelists at the 2019 Community Broadband Summit in March, Curtis Dean, co-founder of CBAN, paused.

The audience of 30 filled a Holiday Inn meeting room in Urbandale. Participants represented eight communities and a couple of small broadband providers working in Iowa, Nebraska and Colorado.

“Most people think of broadband as internet, and it certainly is, but it’s also video, it’s also telephone, it’s also security, it’s also smart home, it could be smart grid infrastructure for electric utilities,” Dean said.

Defining “better broadband” will be different among communities, he said, but there is a list of common qualities the service should meet: fast, reliable, affordable packages to the vast majority of the community, universally available in the region being served, with responsive and consumer-friendly service.

“If your community decides that you can’t check off all five of these, then I would say you need to be exploring better broadband,” Dean told the room.

Now, communities that need help attaining that turn to CBAN and Dean, Todd Kielkopf and Jon Anne Willow.

CBAN was founded in 2018 after the co-founders witnessed a rash of smaller Iowa communities in the 1990s and early 2000s that voted to build municipal broadband networks.

That left them with questions: “Why aren’t more communities who have taken votes moving forward?” Kielkopf said. “In all of these areas, the industry was not, in my mind, well-organized or able to handle the evolution of a decision.”

If those smaller-town city clerks and mayors knew there was a reasonably safe place to ask the right questions, there [might] be enough people that give them the right answers at the right time.”

Todd Kielkopf, co-founder, CBAN

“Every time we’d hear [of] a barrier, we’d think, ‘How would you fix that?’” Kielkopf added. “If those smaller-town city clerks and mayors knew there was a reasonably safe place to ask the right questions, there [might] be enough people that give them the right answers at the right time.”

Why Bother about Broadband?

Whether Iowa is the best-connected state in the nation is open for debate.

A 2018 U.S. News & World Report story ranking Iowa the best state in the nation became a well-cited source for state leaders, and the state’s infrastructure and broadband access — both of which U.S. News & World Report ranked Iowa No. 1 in — played a key role in the report’s ranking.

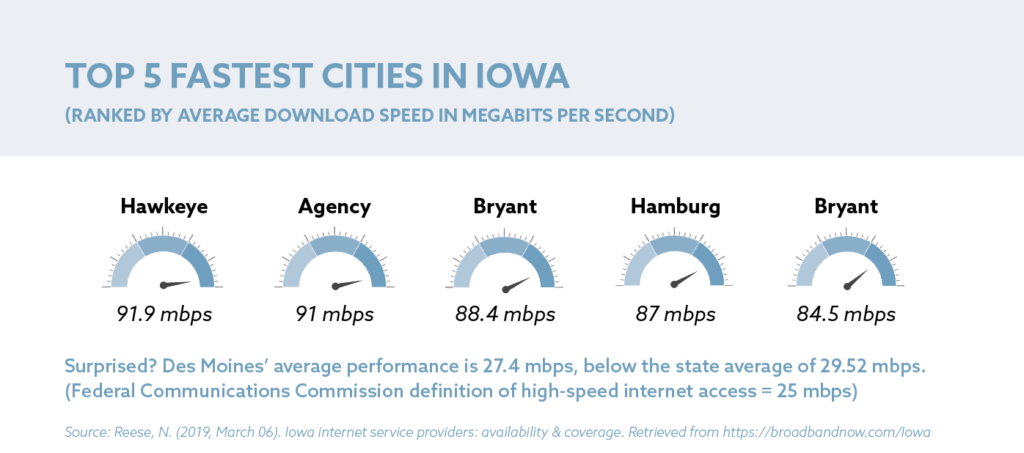

Yet, researchers at BroadbandNow.com rank the state much more modestly as the 33rd most connected state in the U.S., based on how much of the state’s population has access to 25 mbps or faster wired broadband.

The U.S. as a whole doesn’t rate as highly as might be expected on the world stage. The U.S. ranked No. 16 in the world for broadband access as of 2013, according to BroadbandNow.

Iowa is second only to Texas in terms of the number of providers residents can choose from — 417 providers, versus Texas’s 471 providers. As of March 2019, BroadbandNow reports that only 25.8 percent of Iowans have access to fiber-optic broadband services, compared with 77 percent who can access cable, and 88.1 percent of Iowans who can access DSL service.

Good broadband in all of Iowa means accessible service for everyone, Dean said.

“We understand that while we think fiber is great … it’s not going to work for that farm 12 miles out of town for a few years. There’s got to be something better,” Dean said. “Those people need service, and there are a lot of things that can be done through wireless technologies in combination with fiber. It’s not a one-size-fits-all approach.”

Communities can vote locally to form a telecommunications utility — either to study and build their own fiber to the home model, or a modified version, such as a private/public partnership between a community that builds the infrastructure and a private company that manages it.

“There was a wave of communities who took those votes in the 1990s and mid-2000s, and then the planning just stops,” Kielkopf said.

Kielkopf and Dean wanted to offer communities a portal to help leaders begin making the next steps.

“The end goal of all of this, of course, is better broadband as defined by that community,” Dean said. “It shouldn’t be up to a provider’s definition of what is good.”

The fire was there 20 years ago, but it was followed by stagnation — either because community leaders didn’t know how to proceed or because incumbent broadband providers promised to provide better services, cheaply.

“One of the reasons that some of those votes that happened around the turn of the millennium never turned into actual networks is it frightened the [incumbent] providers enough that they made some improvements to their service,” Dean said.

“We call it the ‘good enough’ phase,” Kielkopf added.

The Reliability Factor

To assess reliability, Dean asked summit participants at the Urbandale meeting in March to picture a light switch. The switch allows a resident to turn lights off and on throughout the house at any time of the day.

“You don’t have to decide, ‘I really want to turn on the living room lights, but I better … go turn the refrigerator off because there’s not enough electricity here to take care of my needs,’” Dean said. “If we ran our telecommunications grid the way we have run our electric grid for the past century, you’d just flip a switch and you’d have whatever you needed.”

Yet, that’s not how residents treat broadband providers. The networks of today across rural Iowa tend to be copper-based — and old.

Incumbent companies break up their regional offices into markets, which must compete against each other for limited development capital from the main company office. Older populations in rural communities might also be hesitant to purchase a company’s higher-priced packages, creating less profit incentive for the company to invest in rural markets.

“That doesn’t mean that folks don’t still need reliability … it just means that maybe you’re not going to get it necessarily from an investor-owned utility,” Dean said.

Old copper-based networks can still be reliable — “in some cases, maybe [more] than they were 10 or 15 years ago,” he said, but they haven’t kept pace with popular expectations.

“It’s just physics,” Dean said. “A glass fiber passing light frequencies can move more bits and bytes from one point to another than a copper line.

“There’s a lot of things that can go wrong with a copper network, especially if it’s not well-maintained.”

Dean believes copper networks will still be around Iowa for a while, though — a decade at least, and probably longer.

“Even a copper delivery-based network like Mediacom or CenturyLink is still using a lot of fiber optics in that network. It’s just not all the way to the end user,” he added. “There’s always going to be these pinch points where it goes from fiber to copper, and that’s where the slowdowns happen, that’s where the reliability issues come in.”

Helping Communities Self-Advocate

A community broadband project is not like a potential dog park project. For residents with no experience in the telecommunications industries, the threads of conversation can be tangled up in technical jargon. Giving residents — and community leaders — the tools to ask informed questions comes down to clearly outlining how broadband access can change daily life, Dean said.

“I think it really comes down to communicating the benefits of what you’re talking about in terms of what is important to them,” he said. “What’s important to them is that their children will be able to get their homework done on time without you having to take them to McDonald’s because that’s the only place you can get internet.”

Communities where the conversation fails have commonly turned to outside consultants to lead the charge for broadband expansion, rather than guiding the conversation to explore what the community’s priorities are, Dean said.

“Every community has its own personality, just like every person has a personality,” he added. “You really have to work within that community’s own personality parameters to help you find a final solution. And in some communities you’ll never get there, because that’s not in their bones.”

“I think it really comes down to communicating the benefits of what you’re talking about in terms of what is important to them, … What’s important to them is that their children will be able to get their homework done on time without you having to take them to McDonald’s because that’s the only place you can get internet.”

Curtis Dean, co-founder, CBAN

If small communities are between the proverbial rock and a hard place, truly rural households struggle to make the case for companies to invest in extending fiber broadband their way.

That could be CBAN’s strength. As small broadband providers are planning growth strategies for the next four to five years, Dean and Kielkopf envision using CBAN’s network to connect providers with forward-thinking communities seeking an alternative for broadband service in the next 10 years.

“They might be going right by your community in five years. Or they might do a 10-mile detour if they knew that community [is] unhappy,” Kielkopf said. “They don’t have the staff that’s going to go to community meetings and talk to the champions. So if we can build a virtual place for that, sure. It’s helping those community advocates by actually getting [them] noticed.

“If we can provide places for these conversations to happen, and the stories to be told between the different sectors of the community, then you can actually get people to understand and wrap [their] arms around what the problems are,” he added.