Iowa’s Wallace family legacy of innovation continues

Who’s who in the Wallace family

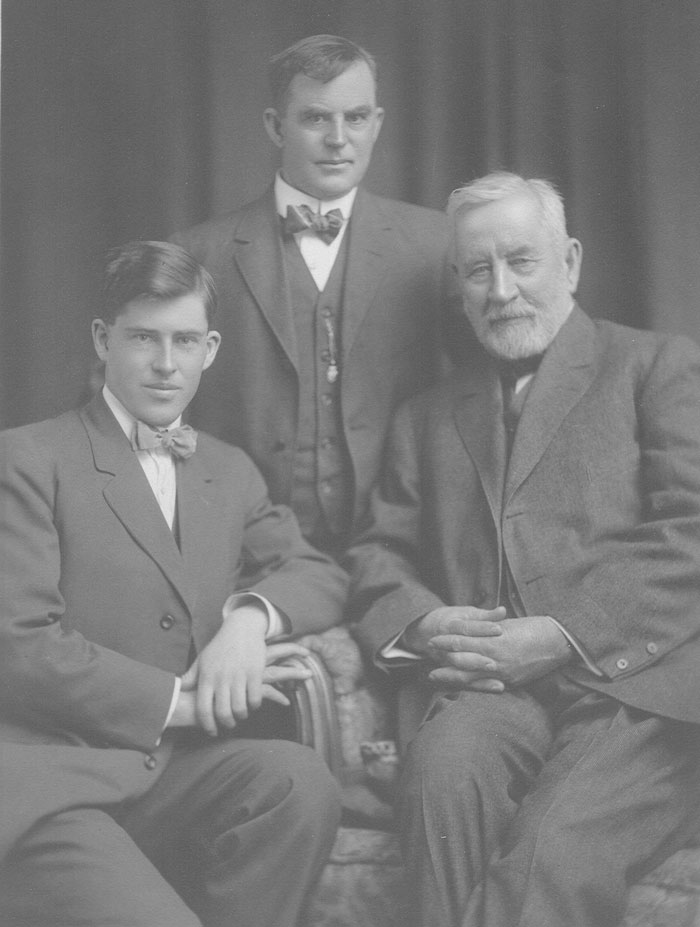

Notable Iowans branch out from the Wallace family tree, but there are several who rose to prominence in agriculture and politics. Here are the four Henry Wallaces to note.

Who is Uncle Henry?

He’s the Henry who brought the Wallaces to Iowa in 1862. He co-founded Wallaces’ Farmer with his sons Henry C. and John in 1895. He became known as “Uncle Henry,” helped establish Iowa State College as an agricultural research institution, and promoted the Agricultural Extension Service.

Who is Henry C.?

Henry Cantwell Wallace was a professor at Iowa State College, editor of Wallaces’ Farmer and co-founder of the American Farm Bureau Federation. He served as secretary of agriculture for two presidents from 1921 until he died in 1924.

Who is Henry A.?

Likely the most well-known of the Wallaces, Henry Agard Wallace graduated from Iowa State College and went to work for Wallaces’ Farmer. He researched corn seed and eventually founded Hi-Bred Corn Co. in 1926, later known as Pioneer, and eventually part of Corteva Agriscience. He served as the Depression-era secretary of agriculture and put in place farm policies and programs for resource conservation and economic stabilization, many of which have remained in place for decades. He was vice president from 1940 to 1944. He became secretary of commerce until 1946, and then ran for president in 1948. He died in 1965.

Who is Henry B.?

Henry Browne Wallace “did for chickens what his father had done for corn,” according to the Wallace Centers of Iowa website, leading the hybrid poultry division of Pioneer Hi-Bred in 1939. His efforts increased egg production.

To learn more, visit wallace.org.

The legacy of Iowa’s Wallace family – innovators, politicians, policymakers, publishers and more – continues today.

The Wallace Centers of Iowa organization reflects the family’s longtime values of local food, sustainability and civility, keeping the Des Moines home on 16th Street and the Country Life Center in Orient.

“What we try to do here is take the legacy that the Wallaces started, and then try to make that relevant to modern life,” said Ann Taylor, WCI’s vice president for marketing and resource development.

The most well-known family members are the Henry C. and Henry A. Wallace (see sidebar for bios), nationally known Midwestern leaders in the 1900s. Wallaces had a hand in establishing Wallaces’ Farmer as the premier agricultural publication, often using it to help steer farm policy across the country. The family started experimenting with developing hybrids of seed corn, leading to the creation of Hi-Bred Corn Co., a forerunner to what is now Corteva Agriscience. Wallaces became students at Iowa State University and held national offices – including secretary of ag and vice president.

“The three generations of Wallaces helped bring about major changes in American farming, food production methods as well as American and world politics,” summed Iowa Pathways, an online learning resource by Iowa Public Television that documents people, places and events from the state’s history.

Local food sources

One way in which the Wallaces’ past and the present connect is through efforts to get Iowans to understand the link between the land and what they eat. There are workshops and classes as well as programs that further the Wallace legacy in this area. These days, WCI holds dinners at the Country Life Center that highlight locally grown food. There’s an agreement with the Food Bank of Iowa for produce. A recent innovation was opening the Mickle Center Shared Use Community Kitchen. It’s a space that can be rented out by food entrepreneurs to test their business without having to go to the expense of outfitting a commercial kitchen.

WCI set trends years ago as well. It was among the earliest CSA operations (community-supported agriculture) in Iowa.

In a CSA, “subscribers” connect with a farmer who grows fruits and vegetables and also possibly provides eggs, dairy and meat. A customer becomes a member of the farm. The products are provided to them at a pickup or distribution point.

“We started that 20 years ago, before people really even knew what CSA even meant. I’m sure there are still people that don’t know that, but it’s become much more common,” Taylor said.

In 2015, U.S. Department of Agriculture data counted 7,398 farms nationally that sold products directly to consumers through a CSA.

With the movement in good shape – and getting back to the present – WCI decided to stop the CSA this year and focus more on its Garden for Good.

“We have set aside one acre of ground at the Country Life Center. We are partnering with the Food Bank of Iowa, and our goal is to grow 10,000 pounds of sweet potatoes for the Food Bank,” Taylor said. “They have a distribution network of 55 counties throughout Iowa. So they’re in a terrific position to get that produce where it needs to go to people who are feeling food-insecure.”

About the Family

“The Wallaces were different. They were part of, but apart from, the general husbandry of Iowa. They were smart and innovative and eager to take the lead. Unlike most farmers of the day, Harry had been to college and was a believer in ‘book farming,’ the application of scientific principles to agriculture. His young wife also had been to college and was trained in music and art. Like most Iowa farmhouses, Harry and May Wallace’s home had no toilet, electricity, furnace, telephone or running water. But it did have books and a piano, and it was brimming with ideas.”

– “American Dreamer” by John Culver & John Hyde

Civility

The Henry Wallaces helped set conversations in the state and nationally about rural life, agriculture, land use and other topics. They did this through Wallaces’ Farmer as publishers and through Hi-Bred Corn Co. as businessmen. As politicians, they were not afraid to tackle hot topics.

For instance, in 1948 Henry A. Wallace ran as a third-party candidate for the presidency. Because of his relationship with black renowned scientist George Washington Carver, he refused to speak before segregated crowds. (His life and views are captured in “American Dreamer” by John C. Culver and John Hyde.)

“He was very visionary for his time, and practices that we think are just standard now, you know, were really revolutionary in his day,” Taylor said.

Henry A.’s presidential run with the Progressive Party ran into lots of trouble for some of his political stances. It ultimately was unsuccessful.

But the commitment to public service and community remains.

WCI offers events on leadership and civility. One example: A 2019 luncheon series tackles women in leadership. “Ground Breakers: Women Leading Change” provides a forum for lunch at the Wallace House with a presentation on a hot topic – this year the list included Kirsten Anderson, an advocate for harassment-free workplaces, Beth Shelton, the Girl Scouts of Greater Iowa CEO who instituted an “infants at work” program, and Antoinette Stevens, a cybersecurity analyst who seeks to help low-income Iowans find new careers through coding.

“I think [their legacy] is trying to find common ground, working for the betterment of all. Public service was a huge component of their lives,” said Taylor.

The Wallace Centers of Iowa is not owned or operated by the family, but members are part of the board of directors. Originally, the Country Life Center and the Wallace House operated separately, but the organizations merged in 2009.

“The three generations of Wallaces helped bring about major changes in American farming, food production methods as well as American and world politics.”

Iowa Pathways

Don’t leave out Wallace women

It wasn’t just the Wallace men who blazed trails in the state.

“We also try to lift up the women in the family as well. One thing that we do in particular that focuses on the women’s side of the story, so to speak, is our Hearts and Homes Historic Teas,” Taylor explained.

The teas stem from Nancy Cantwell Wallace, wife of “Uncle Henry” Wallace, who would often contribute to editing Wallaces’ Farmer right from the house on 16th Street. She handled the “Hearts and Homes” section. (In fact, she was one of the first female journalists in Iowa and was a founder of the Women’s Press Club.)

Taylor researches old issues of the publication, picks a theme and runs an event around it. There are readings and discussion questions.

“People talk about those questions then at the table and make conversation. That’s really kind of, in a nutshell, what the family believed. If they could just gather people around the table, you could find some common ground, you know, if you’ve worked hard enough at it. Every program that we do, we try to bring that element in,” said Taylor.