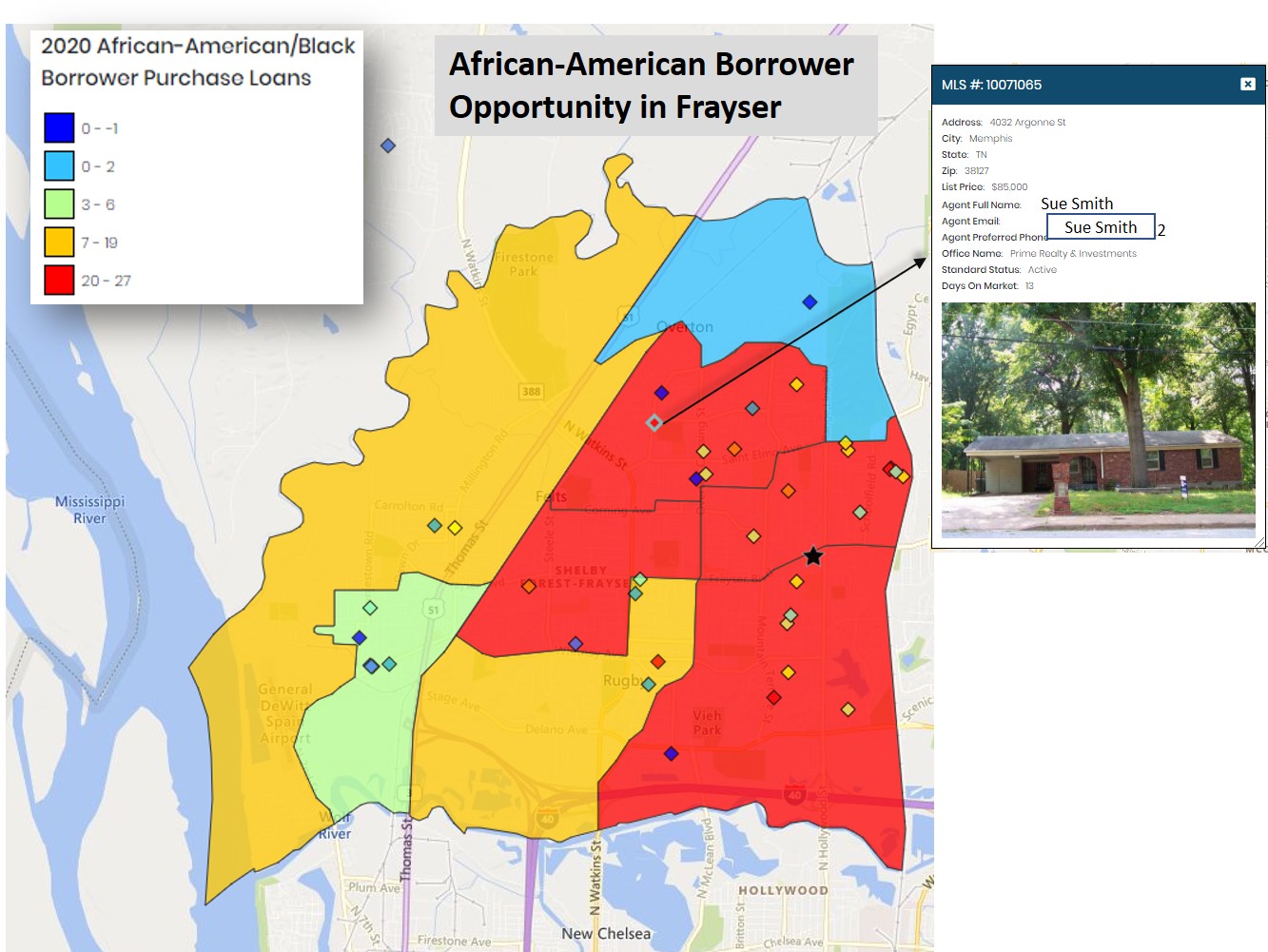

This census tract map of the Memphis, Tenn. neighborhood Frayser provides insight to a bank (whose branch is indicated as a star) about the 2020 purchase loan opportunities to Black borrowers near their branch location. iEmergent’s Mortgage MarketSmart – Diversifi platform uses a type of heat map (see legend) to quantify and pinpoint where there are opportunities for Black borrowers. The bank had not yet originated loans in 2020 to minorities in this community, despite having a bank branch within it. The map also shows active real estate listings (diamonds on the map) with Frayser and identifies each listing agent, thereby helping the lender identify realtors, nonprofits and other community resources in the community — one of many strategies a lender can pursue to improve lending to Black households in their communities.

Image provided by iEmergent.

The road to affordable housing in U.S. communities actually resembles many different paths. Wage equality, renters’ rights and zoning ordinances all have a role in local market affordability — and through a national coalition, one Iowa company is recruiting local mortgage lenders to invest in their own communities.

“Banks shouldn’t only be there for wealthy people or upper-middle-class people,” said Laird Nossuli, CEO of mortgage market intelligence firm iEmergent, which is based in Urbandale.

iEmergent is now a national partner in Convergence, an affordable housing initiative launched in spring 2020 and led by the Mortgage Bankers Association. iEmergent joined during the launch of Convergence Memphis, a pilot project between the MBA and the Tennessee Housing Development Agency to strengthen Black homeownership in the Memphis metropolitan area; this fall, the initiative will also begin planning Convergence Columbus, and is in the process of identifying target neighborhoods in Columbus, Ohio.

Using iEmergent’s Mortgage Marketsmart web application, Convergence is uncovering detailed maps combining census tracts, public home loan data, current house market listings and iEmergent’s own forecasts of future lending opportunities. When shown the data — and how few investments local banks have made in their own neighborhoods — Nossuli and Convergence leaders hope it pushes local lenders to act intentionally to exceed standards established by the Fair Housing Act and Community Reinvestment Act.

“I’m trying to empower lenders to be empowered in their community,” she said. “I’m trying to change the conversation to be, ‘Look at this opportunity that exists in these other markets.’ They have to deal with this, they have to start being more compliant. But I want to help them be compliant in a way that doesn’t blow their business model, because they will not do it if they do it at a complete loss.”

HOME TERRITORY

In the Memphis neighborhood of Frayser, the median income of residents is $27,000 annually. The average property value sits at about $40,000. Around 80% of Frayser residents live below the poverty line, and the majority of those residents are Black, Nossuli said.

“When you go to Frayser, you realize there are no grocery stores. There’s no public transportation, there’s no good schools close,” Nossuli said. “There’s a lot of people who rent, but when the house gets to a point where it is so dilapidated, rather than fixing it, it’s got such a low value [that] the landlords vacate it. It goes into foreclosure.”

That meant that Frayser and other Memphis neighborhoods targeted by Convergence had housing stock available, but much of it is not livable. Banks looking for lending opportunities targeted outside neighborhoods, spiraling the habit of investing outside Frayser — overlooking the housing stock and lending opportunities that does exist in the neighborhood.

“Everyone said, ‘I can’t lend in Frayser,’” Nossuli recalled.

Yet, through public records iEmergent could identify current houses on the market in the neighborhood, sort them by price or by realty agent name, overlay the last year’s worth of loans offered by bank, and forecast how many loan opportunities would be in the neighborhood in the next year.

During a demonstration in front of local loan officers this summer, Nossuli brought up a census tract map of Frayser and identified one anonymous bank branch located in the neighborhood borders.

“We put that bank’s 2019 purchase loans [on the map]. They had one purchase loan in the neighborhood they’re in,” Nossuli said. “Here is a bank, smack-dab in this neighborhood, and they did one loan in a year to a household. That’s not right, but that’s the reality.”

COMPLIANCE

Nossuli points to two benchmarks that judge whether lenders are serving their own community: the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977.

The cost for noncompliant lenders can be severe: In 2012, Wells Fargo & Co. agreed to pay $175 million after the U.S. Justice Department alleged the company charged Black and Hispanic customers higher rates on mortgages compared with white borrowers with similar credit profiles.

But inequality in lending practices can also rise quietly, such as if a lender’s policy is rejecting substantially more loan applications from one protected class of applicants than from another class. Those practices are harder to uncover but can lead to systemic inequity in lending — which can potentially result in examples like the Frayser bank branch.

Lenders should see that as a problem for their business, Nossuli said.

“In the past, redlining was the act of lenders specifically not lending in these red zones. What [iEmergent] is doing is we’re flipping it — we’re saying, ‘Let’s focus on lending in these red zones,’” Nossuli said. “What I’m trying to help them do is not say, ‘Oh, we can’t be profitable in Frayser.’ I say it doesn’t matter if you’re profitable in Frayser, it matters that you’re profitable in Memphis. If their margins are wider and bigger in the wealthy neighborhoods, they can have really thin or negative margins in the communities that need their help — but in general, that’s a healthy business in Memphis.”

Once lenders in Memphis can see gaps in their service through the Mortgage MarketSmart platform, Convergence partners can help them develop practices to reach the community. Loan officers can partner with Realtors who are already in the neighborhood and know the local market; Realtors can be informed of local organizations offering down payment assistance programs to potential homebuyers with steady jobs.

“When I show them this tale of two futures and show them this new way — what they have to gain — they are jumping in. It’s made me realize one of the reasons that lenders haven’t done this is because they haven’t had the insight to do it,” Nossuli said. “That’s the role we bring to the table.”

Pilot programs by Convergence are still in development, but iEmergent’s process could work with willing partners in any community, Nossuli said.

“This kind of data gives [lenders] a road map and a targeted plan for how they can start doing better. And the thing is, even though I’m talking about one lender, when you have 10 lenders getting better, you have communities being served,” she said.