How Iowa suppliers contributed in the race to build personal protective equipment

Early on in 2020, headlines of product shortages began hitting the screens and newstands. Consumers worried about finding diapers, toilet paper and disinfectant spray; organizations employing essential workers were suddenly seeking personal protective equipment for their staff.

Chris Hill, the technology program director at Iowa State University’s Center for Industrial Research and Service, recalled seeing a flood of new customers — such as nursing homes and care facilities — trying to get personal protective equipment from manufacturers at a time when shortages were already hitting the strained emergency medical workforce.

As store shelves emptied, many buyers were turning to online marketplaces like Amazon, where the product’s quality was in question. “Buyer beware,” Hill warned.

If Iowa organizations were going to pull through the pandemic with appropriate supplies, they would need help. By the end of 2020, CIRAS and other manufacturers had built a domestic supply chain from the ground up.

“We have companies in Iowa that make socks. Believe it or not, socks means cloth, means sewing, so that’s a face mask,” Hill said. “If we look at face shields, you’d have a piece of plastic film that needs to be cut to a shape, or what we say in the industry, die-cut. So when you start looking at companies in Iowa that die-cut things, there are a few rather large players there.”

LEVELING UP PRODUCTION

When the pandemic hit, the company One World Supplies didn’t exist at all. The five founders were coworking at Gravitate Downtown in Des Moines and started reading news reports of personal protective equipment shortages. With varied professional backgrounds, Anisul Huq, Camille Renee, Julien Duhautois, Tim Vastine and Yolanda Wei established OWS early on to begin addressing those shortages by connecting U.S. customers to suppliers, beginning with masks and expanding to 13 types of medical-grade products.

The first four months of work identifying manufacturers and navigating imports were chaos, Huq said.

“Some of the people that we met who were making stuff, the quality wasn’t at the level [needed]. They were too new to get the certifications they needed for us to even look at proposing them to a hospital,” Huq said.

By early 2021, OWS established foreign and domestic partnerships to manage supplies for clients. The first was with a Chinese transportation company to handle the exporting and transportation documentation involved with delivery to the U.S. Later in the year OWS and Armbrust USA, based in Texas, struck a deal to supply N95 masks to OWS’ national clients, including the Mercy Health Network in the Midwest.

CIRAS began identifying Iowa-based manufacturers who could quickly pivot lines to personal protective equipment components. New decrees issued by the federal government lessened some of the regulations for companies entering production of a few items, and CIRAS staff worked with state officials to develop basic designs that could be produced by any new manufacturer for certain items.

“We stepped back and said, ‘What are some of the basics that we know looking at history?’ History tells us that face masks, face shields, gloves, goggles are all items that people have used, governments have used in the past to reduce the transmissions of certain diseases,” Hill said.

Manufacturers shipped product prototypes directly to Hill at CIRAS, who worked with Mary Greeley Medical Center representatives in Ames to evaluate the products’ effectiveness for medical workers.

By the end of 2020, CIRAS worked with about 100 manufacturers; about 10 were producing products in the tens of thousands. Some businesses simply had staff members sewing masks out of their home for local organizations. Through the website, CIRAS directed companies seeking PPE to contact information for manufacturers producing PPE.

“We were getting calls from nursing homes and some smaller hospitals asking for help, and in all cases we had products to give, we simply gave it to [them],” Hill said.

Producing the main components of face shields — a plastic visor attached to a headpiece, which protects the user’s face from aerosol particles — took 10 days for CIRAS to coordinate the manufacturing line launch. Online, the product was averaging $6 to $10 apiece, although Hill saw some outlets selling them for $30 apiece.

“When you have schools, nonprofits, care facilities, they don’t have that in their budgets. Ten percent of the cost is a lifesaver to some of these places,” he said.

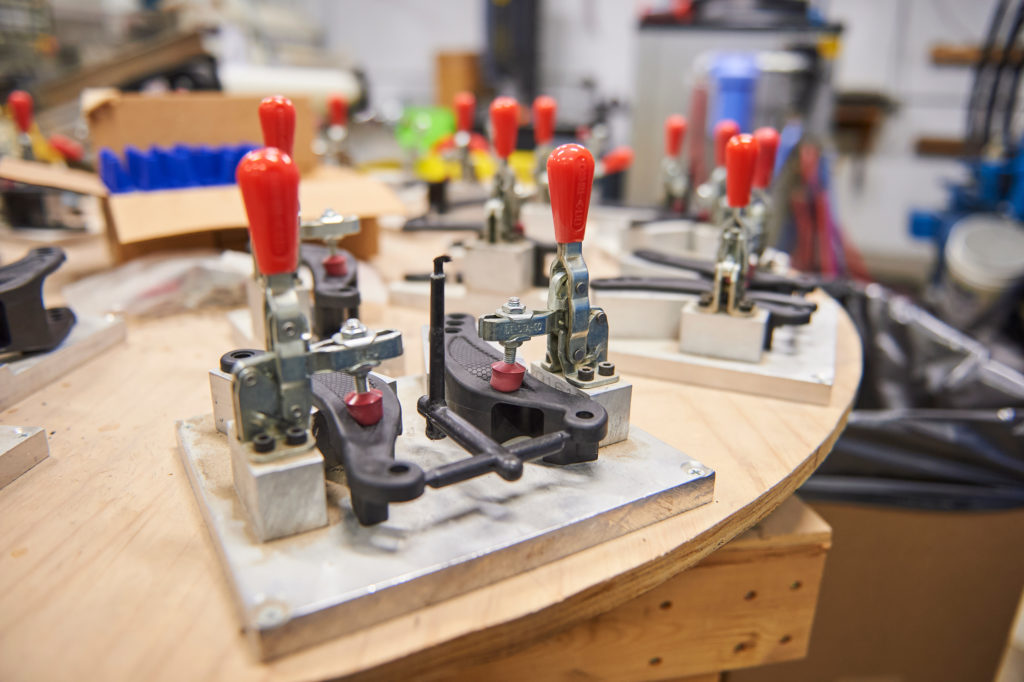

ISU designers developed a dozen halo design configurations for the face shields within the Digital Manufacturing Lab Powered by Alliant Energy, which houses 3D printers at CIRAS. Meanwhile, department staff quickly connected three Iowa manufacturers — Metalcraft and the Dimensional Group, both of Mason City, and Angstrom Precision Molding of Ottumwa — who could mass-produce pieces of the final product.

By late April the partnership was producing face shields 24 hours a day, seven days a week — and the state of Iowa ultimately bought over 1 million face shields produced by the partnership over six months’ time, and distributed them through the National Guard.

“Even now there’s some fear, but back then there was, I think, even more fear, because there were more unknowns,” Hill said. “We actually upfront paid for some of that material so that the company didn’t have to assume that risk, because we knew it was the right thing to do.

PLANNING FOR 2021

After more than a year operating in a public health crisis, businesses now have some time to examine whether they will continue offering the product lines or return full time to their pre-pandemic business model. CIRAS staff began working with Iowa companies in late 2020 to assess how sustainable their newly entered markets are for the businesses long-term.

The government could decide to play a larger role in maintaining a larger domestic supply chain, Hill said. The federal government could commit to purchasing baseline amounts of PPE products each year at a set price, making it worth a manufacturer’s cost to stand up and maintain manufacturing lines for facemasks, gloves and gowns even as the pandemic is brought under control in the population.

“That price point that they would pay is probably going to be higher than what they would buy if they just went to Asia and bought Asian-made PPE,” Hill said. “That cost differential is part of national security — there’s a price for that.”

Predicting the needs of the next few months is an uncertain business for both suppliers and their clients, Huq told the Business Record in late January. Hiring for a high-growth company has been a challenge: OWS currently has five full-time employees, and at its peak growth in mid-2020 had nine employees on payroll to manage overnight calls to China, paperwork and factory vetting.

“That’s one of the things where I have to lean on my mentors heavily,” Huq said. “This is my first time running a high-growth company. I learned a whole bunch of limitations that I have individually, that I had to get better at, and hiring was on the top of the list.”

OWS began transitioning from importing multiple PPE products to identifying U.S.-based manufacturers of N95 masks and building a domestic supply chain. OWS is also examining whether the company can develop computer visioning-based software solutions for health care clients, but the N95 mask supply chain will likely remain as a core service.

“I still expect demand to be there, but I don’t expect the scale to be anything like hospitals placing orders of millions of these at a time. I heard some hospitals were placing orders for 20 million back in the day — that’s not going to happen anymore, but they will be more expensive again because the resources aren’t there,” Huq said. “There’s no telling, and it’s kind of like everyone’s taking it a month at a time. No one really knows if it’s going to clear up, or if numbers are going to get worse and worse.”

It’s a calculation most supply chain businesses have to make, Hill said.

“Every company is going to have to make that determination for themselves. The role CIRAS is playing is helping them understand the regulations that could be in play — what they need to do to prepare for that, and to help, in some cases understand the market, and if it is really viable to stay in that market,” Hill said.

“It’s always been what’s the next project, what’s the next thing you need,” Huq added. “At the end of the day, hopefully we helped a lot. That’s the goal, but in the moment you just stay and do the work.”